Tweet

Last month when I asked ‘Does the classical music industry need to innovate to survive?’, I must admit, I wasn’t completely sure how it would land. I even started by rationalising to myself that now is the right time to think about the big questions. I knew that many colleagues were (and still are) mourning for programmes that will never be realised – believe me, being similarly just weeks from the classical season launch in Birmingham, I know exactly how this feels. I also knew that for some the idea of even starting to think about a different kind of future would be difficult to stomach. However, I was (and still am) convinced that this is an important conversation to have.

The day after that blog post, I felt an element of reassurance as Arts Council England CEO Darren Henley asked ‘What comes next?’ where he too acknowledged that “We’ve all had to face up to the fact that none of us will be returning to the pre-pandemic world: our sector will need to change.” He went on to explain that we were entering the ‘Stabilisation’ phase of a three-phase roadmap – the focus would now shift to “supporting [us] to adapt business models and to reopen when it is safe to do so” – and announced the launch of a survey with the sector to inform the Arts Council’s work with Government in response to the COVID-19 crisis. And, on the same day, the much talked about Government Cultural Renewal Taskforce met for the first time. Suddenly, the day after my post, not only did it feel like now was definitely the right time to be having a conversation about the future of the arts, but it felt like the conversation was already starting.

The Cultural Taskforce had barely begun when questions were being asked about whether its membership consisted of the right people. This included questions asked about whether a centralised Taskforce is the best approach, and rather that people who work in the sector should devise solutions locally. As I reflected on this, I couldn’t help but wonder whether we as a sector need to bring this issue back to ourselves. Put simply, in our own organisations, are we ensuring the right people are contributing to the conversation about the arts? Not simply about the post-lockdown future, but about the work of arts organisations more broadly.

Over the past few weeks I have been reflecting on, and engaging in conversations with various friends and colleagues regarding, the concept of bringing different voices into conversations. Recognising that the ability to do this will be different for every organisation, below is a compilation of my thinking highlighting three groups of people where organisations of different shapes and sizes have, and could, shift the boundaries to enable them to contribute to the conversation. As before, this article has a classical music focus, however I believe could be relevant to arts organisations working in any artform.

Artists as co-curators

During my time on the Board of Sinfonia Cymru, the organisation established Sinfonia Cymru Curate – a Youth Board and creative hub of young musicians and arts entrepreneurs, from within and outside of the orchestra. The young people within Curate were given the freedom to curate experiences that they felt appealed to other young people and, unsurprisingly, the result was much more relevant to the group of people the orchestra was trying to attract. Curate continues to this day ensuring ‘the creative minds of musicians are brought to life when they become curators of their own concerts’.

But what happens after these musicians progress into the full-time working world, and make the move to more established orchestras? The idea of orchestral musicians as co-curators, of programmes or indeed the future, does not appear to be commonplace amongst orchestras, yet this level of creative thinking does not simply disappear. There are some who have long been calling for artists to have more of a voice. In 2015, violinist, presenter and now Artistic and Educational Director of the National Children’s Orchestras of Great Britain Cath Arlidge asked ‘Are our orchestral musicians ‘violin operators’ or ‘evangelists for our art’?’. Similarly, last week I joined an informal group meeting consisting mostly of artists, to discuss classical music during COVID-19, and listened as these artists passionately voiced their opinions on the future, and their role within it. So the question is why are they not being heard? Isn’t it the responsibility of established institutions to listen to artists? And in not doing so, are we failing artists?

There are some who say that the role of artists is purely to perform, and that the responsibility for dreaming up the future is the job of CEOs and Artistic Directors. However, working with artists as co-curators does not remove the need for such leadership roles, it merely shifts the purpose of those roles. As I picked up from my conversations over the past few weeks, the role of a leader in this context becomes one of creating a framework to which the artists that are brought in can meaningfully contribute.

The truth is that artists have been incredibly creative during lockdown – they have animated our streets, built connections, and brought communities together. So, whether it is an orchestra of 80+ musicians, or a venue or festival working with smaller groups of artists, as organisations demonstrate a shift towards work that is more local and more embedded within communities, shouldn’t the opinions of artists – particularly those that live in those communities – become even more important?

Administrators as contributors

So far in my career, I can only think of one occasion when organisational hierarchy was discarded, if only temporarily. During my time at Town Hall Symphony Hall, we produced Symphony Hall Inside Out – ‘a free festival of unexpected sounds in unexpected spaces’. The Working Group leading on the project were chosen as a result of their creativity, regardless of their position in the organisational structure. The result was a flexible group of creative people thinking outside the box about new ways to attract new audiences to a traditional venue. What if this approach, of empowering more voices from the wider workforce, was stretched beyond a single creative project? What if the views of members of the administration were brought into an organisation’s visioning exercise, for instance? I can already hear the many reasons why this simply won’t work – “planning by committee will breed chaos”, “everyone’s role is predefined”, “organisational hierarchy exists for a reason”… Surely, there are other ways.

When thinking about new solutions, I often look to creative companies outside of the subsidised arts. Introducing Angela Ahrendts, former Senior Vice President of Retail at Apple who carried out the largest crowd-sourcing exercise across 67,000 retail employees to contribute to a refresh of the overall vision for Apple’s retail division. In an interview with LinkedIn’s Daniel Roth, Angela explained that she simply asked them “…what did they feel [Apple] should be doing, not just in their stores, but also to help impact communities”. The result of these ideas were 7 pilots (which were not far away from the company’s overall values). Fast forward to 2020 and, one of those initiatives, ‘Today at Apple’, now boasts 250,000 sessions per quarter attended by millions of people.

In a later interview at the Commerce & Creativity Conference, Angela explained, with hindsight, why she took that approach:

If you are a leader, you listen… Ask the next generation… they think differently… My ego doesn’t need to say that every idea was my idea… It’s easier, the higher up you get, to say, ‘No’. ‘No, it’s too expensive,’ or ‘It’s too complicated.’ But we had a young council and they would dream and I would tell my direct reports, ‘It’s your job to execute those dreams’… Is it a top-down dictatorship or is your job to listen, connect, enable? That’s kind of how I’ve looked at it: I’m there to serve the vision of the team.

Angela Ahrendts (former Senior Vice President of Retail, Apple)

Audiences as collaborators

In my previous blog post, I talked about the work being carried out by cultural sector consultants Indigo regarding audience attitudes towards returning to live events. They simply asked the people – 86,000 of them – how they would feel about returning to live events post-COVID-19. Under normal circumstances, how often do we just ask the opinion of the people whom we are producing experiences for?

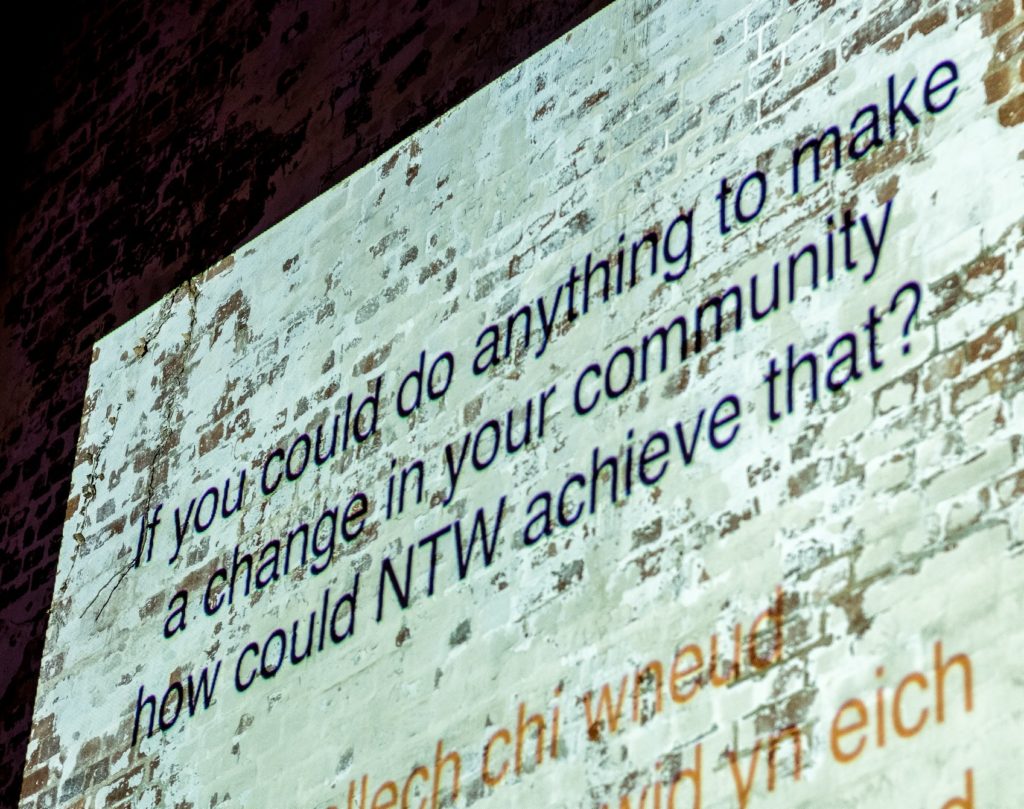

For the last 10 years, National Theatre Wales (NTW) has not only done this, but has consistently invested in ensuring the voices of wider society are contributing to the conversation about the future of the company, via its TEAM initiative. Last week, I sat down (virtually) with NTW’s Head of Collaboration, Devinda De Silva, to find out more about why the initiative was created, how it works in practice, and what organisations might want to consider when developing initiatives involving the community as collaborators. We started at the beginning of the company’s life, 10 years ago, and I was surprised to learn that this way of working was not an evolution, but was in fact part of the company’s DNA from day one.

“When we founded the company, we had an opportunity as a new organisation to look at how the traditional participation or engagement arm of an organisation usually works” he opened, before going on to explain that TEAM was about “[creating] a different relationship… a relationship where the community could feed into the decisions the company made…

…It’s about shifting the power balance between arts organisations and the communities we are there to serve…”

As Devinda continued, it was increasingly clear that NTW has made community absolutely essential to its model. TEAM members feed into the organisation, from creating work, marketing work, and developing audiences. Furthermore, the TEAM Panel (13 TEAM members in Wales who have even deeper input) feed into every aspect of the organisation from strategic planning and interviewing, to public speaking and developing shows in areas such as Pembrokeshire and Wrexham. But ultimately what is taking place is so much more than that. NTW are “developing people as leaders who can be a catalyst for change”.

Even when I asked Devinda what success looked like he explained that, “It’s about the journey of the individuals… and the connections people make… [When the individuals are later] developing skills further, that they first cultivated as part of TEAM. This is one of NTW’s contributions to the creative ecosystem in Wales”.

Credit: National Theatre Wales/Ben Manning

In the spirit of sharing learning, we rounded up our conversation by talking about what organisations might wish to consider when developing similar initiatives involving the community as collaborators.

It takes a lot of time. You have to be prepared to go in, spend time in those communities, go to them, and not expect them to come to you. You have to be genuine with your offer. You can’t go in and get what you want, and then focus somewhere else. You have to be mindful of the work you do. [Furthermore, this has to be] a whole organisation – from top down – way of working which everyone needs to buy into. You need buy-in from the whole organisation, otherwise it’s hard to do it meaningfully, and genuinely, and have the impact you want to have.

Devinda De Silva (Head of Collaboration, National Theatre Wales)

Following my conversation with Devinda, I started to think more and more about ‘buy-in’. It is true that a whole organisation needs to philosophically buy into this kind of direction but, honestly, I think the company also needs to literally buy in in terms of resource. As Devinda says “it takes a lot of time”. Organisations need to invest in people for the long-term, with full support of the organisation, to be able to deliver this work, so that genuine, meaningful relationships can be built.

The key takeaway is that enabling contribution of different voices can bring profound benefits to an organisation and its work. However, whether it’s artists as co-curators, administrators as contributors, or audiences as collaborators, not all of these approaches will be appropriate for all organisations right now. If the above examples simply change attitudes towards the traditional roles of these groups of people, then that in itself is a positive outcome. But taking a longer term view, enabling a range of voices and empowering them with the tools to bring about positive change will cultivate future leaders.

The Conversation

4 Comments

Add Yours →Great thoughts Toks. I think William is right – if I have understood – that those conversations need curating and supporting and shepherding – by somebody. Who? It takes a lot of skill and selfless stamina to be the supportive glue that holds the creative conversations and projects together. In widely spaced geographical communities, this is often undertaken by older, maybe retired people with bags of skill, motivation and goodwill. But they tend, especially in Wales, to be White, Monoglot, Old and Middle Class – and they have limited shelf life, unfortunately. My feeling is that – though it will take time – early years Primary education is where we have to plant the seeds of creative ownership, confidence, expertises and curiosity, in the minds of a young, diverse and potential-rich population. And provide huge support to their teachers and parents, from age 3 or 4 till end of life, up to 100 years later. Just think of the possibilities.

Some great points here. Of course, involving artists in curation is often done at the initiation of an enlightened management team – it doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In the case of Sinfonia Cymru, it took an imaginative and inclusive management team to devise and realise the idea, and to guide and develop the project. It wouldn’t have happened without them, and their commitment to the project is part of the reason it’s still around now.

We should also be wary of the notion that simply involving artists will make projects relevant. Because of their highly specialised training, classical musicians often find it hard to make their work relevant to a wider audience in my experience, lacking the knowledge of a wider cultural context that would enable them to understand what cultural consumers want from an event. Of course there are noble exceptions, and the same issue also exists within management, which is often also hampered by the same narrow field of vision.

Toks you make my heart leap for joy. As a performing artist who celebrates creative engagement, I have long felt severed from sharing and communicating in circumstances which did not feel driven by the wheels of money and meritocracy as its agents and as a cellist who has been privileged to perform around the world I have felt keenly that the role of musician is already increasingly isolated from the narrative of transformative alchemy which we wish to communicate. I imagine that because of the fleeting nature of live performance – one can not retain a physical element of sound – that it does not sit easily in our consumer world and therefore there is less hunger for it and the possibility of transformative power dwindles. I am filled with hope reading your words, thank you x

Great blog, Toks.

I agree that different and a broader range of voices can help an organisation to think in a refreshing way.

The more organisations can enable these different conversations, the better. It is a sign of great confidence if organisations can do that. The trick is sustaining it and acting on what it yields.